The Models that Made the Models

A Collections Chronicles Blog

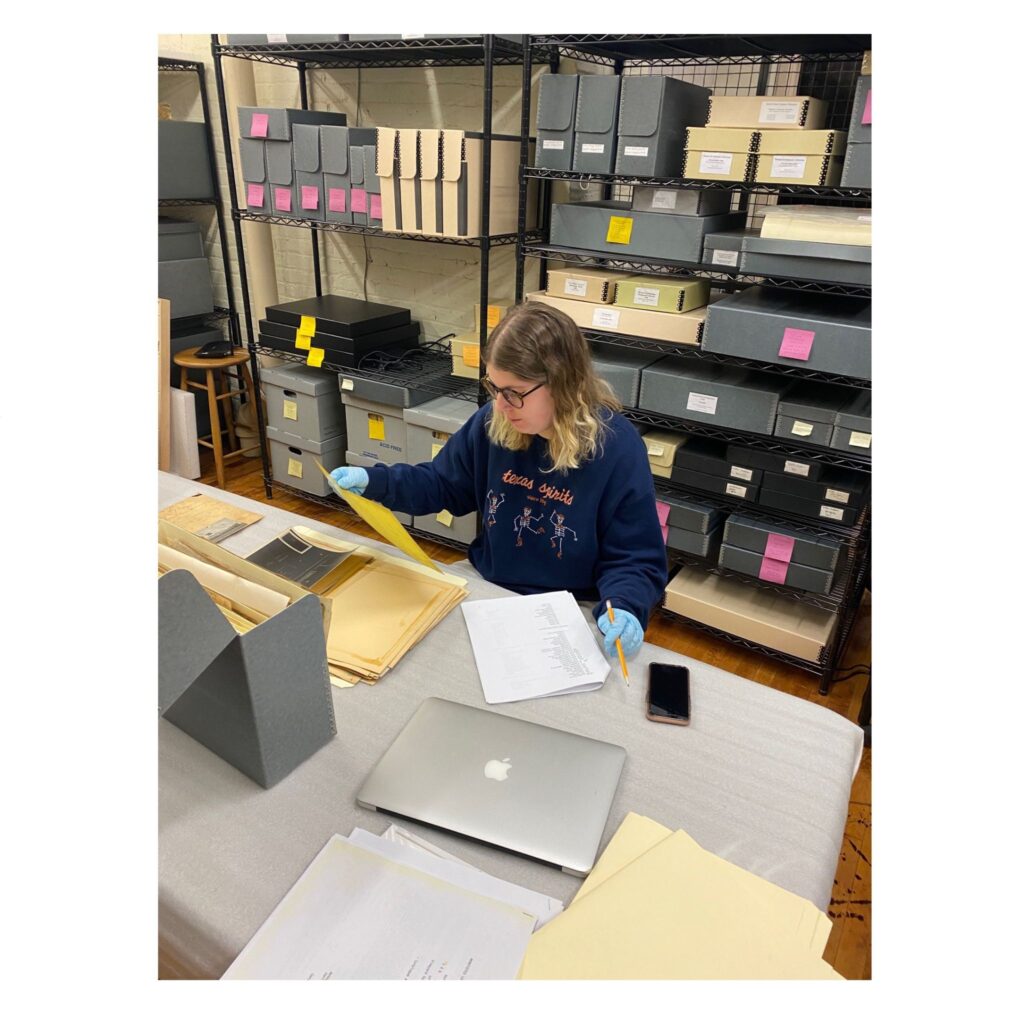

by Kenzie Grogan, Collections and Curatorial Intern

December 15, 2022

Deep in the South Street Seaport Museum’s collection sits a cabinet filled with hundreds of pattern models of ocean liners created by the shop of Charles K. Van Riper of Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts.

I was first drawn to the simple pattern ship models because of one characteristic that set them apart from all the other ship models in the Museum’s collection; they were never meant to be seen by the public. Yet, they are a vital part of the collection as they represent a history of almost all the ocean liners that visited the United States in the early to mid-20th century, and were crucial to the operation and success of Charles K. Van Riper and the Van Ryper model shop.

Over the course of its life (1933–1962), the ship model shop produced around 15,000 vessels. These vessels traveled all over the world, and even landed in the hands of two United States’ Presidents. Below is the story of this amazing model maker and my voyage into cataloging this recently revisited Museum collection.

Charles K. Van Riper and His Ship Model Shop

Charles K. Van Riper (1891–1964) was originally born in Paterson, New Jersey, and had quite a varied life before settling in Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts. He once was a newspaperman, a free-lance writer, an inventor, a playwright, a soldier, a baseball maven, and one of the founders of the nation’s first amateur softball league.

How did he end up running a small ship model shop in the Northeast? Well, a horse fell on him while playing polo in California. This led to the family traveling East to spend time with relatives. While visiting his brother, Donald Van Riper, Charles and his wife Helen fell in love with the little island of Martha’s Vineyard.

Inspired by his son, who inquired as a small child as to what a ferry is, and his lack of physical ability due to his accident, Van Riper built a small model of the ferry Naushon from scrap pieces of wood and metal. The inquisitive mind and entrepreneurial spirit that he was, Van Riper wondered if he could mass produce scale ship models of quality. This idea led to the opening of his ship model shop in Vineyard Haven, using the traditional Dutch spelling “Van Ryper” (to inform pronunciation), in 1933.

Charles K. Van Riper holding a model steamer of Martha’s Vineyard, larger model is American President line C-3 freighter, built to same scale, 1956. Image courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum

Van Riper hired skilled craftswomen and craftsmen to work in his two story wooden building on Beach Road. The shop ran similar to a Ford assembly line. Models were crafted out of poplar wood, brass, and automotive lacquer. Each craftsperson had their dedicated task, such as drafting plans, cutting hulls, or spraying paint. This meant each model was made efficiently and in batches, like a “mass-production in miniature.” The results were high quality models that the average American could afford.

Another unique aspect developed by Van Riper was his stance that models did not need to include every detail of the ship, but simply “enough.” This meant that each model only needed as much detail as could be seen from a distance of two to five miles away, when viewing the actual ship.

Left: Craftswoman working in the Van Ryper shop

Right: Craftsman working in the Van Ryper shop.

Images courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum

While boat-lovers could request models of their personal yachts and favorite ships, a popular production of the ship model shop was the Travel Series. Marketed to people as “Models of Ships on which You’ve Sailed” the series featured simple models of vessels of major passenger lines. The models served as reasonably priced keepsakes for travelers who wished to remember their sea voyages. The models were all of a standard length of nine to eleven inches. This meant an inch represented about forty-five feet on the actual ship. Larger ships had to use an even smaller scale, where an inch could represent around sixty-four feet.

Around 1938, the model ship shop started receiving requests from those involved with marine national defense and readiness, like the Moore-McCormack shipping line and the U.S. Maritime Commision. The production of recognition models, which were used to teach sailors and naval aviators how to recognize enemy warships by their distinctive silhouettes, was active, and the Navy hoped that the models would help new recruits from misidentifying enemy ships or mistake Allied vessels for Axis ones. These new commissioned models paralleled the Travel Series in that they rendered the ships as they would appear from miles out at sea, and they kept the model shop on its feet. Van Riper was running double shifts at its peak to keep up with its contracts. The shop even produced model representations of the entire Imperial Japanese Navy, which consisted of 2,300 ships!

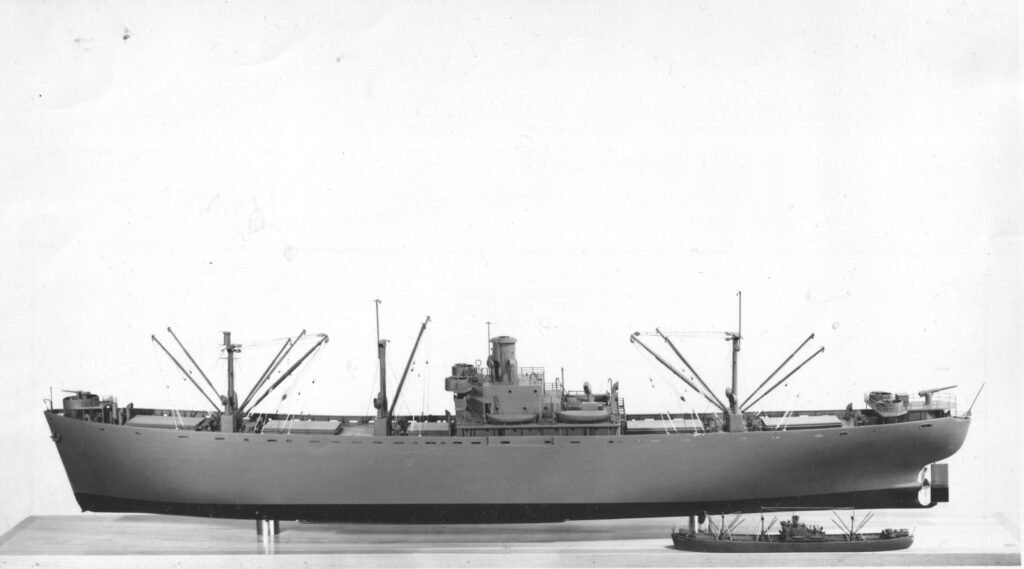

Two models of a Liberty Ship, the famed World War II freighter. President Roosevelt owned a Van Ryper model in the larger size. Image courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum

After the war, the country saw an increase in prices and a decrease in sea-travel. This meant the prices of models increased, from $5- $6 in the 1930s to between $10- $15 post-war, making the models less accessible to some. A decline in those traveling by ship also meant the demand for souvenir ship models decreased. To compensate, Van Ryper branched out into different areas like model-embellished lamps and wastebaskets, desk boxes, wall plaques, wooden fish, and self-assembled model making kits.

The Van Ryper ship model shop closed down in 1960, following health complications of Charles K. Van Riper. Its showroom continued to stay open for two more years.

The Collection

The South Street Seaport Museum acquired a collection of 285 Van Ryper ship models in 1982 from Anthony K. Van Riper, son of Charles K. Van Riper. Outlined in a letter to the Museum, Anthony states that he included models built between around 1938–1950 called “pattern models.”

The donation also included a number of archival materials that pair with the models, including research material on steamships, photographs, deck plans, postcards, and steamship company advertising brochures.

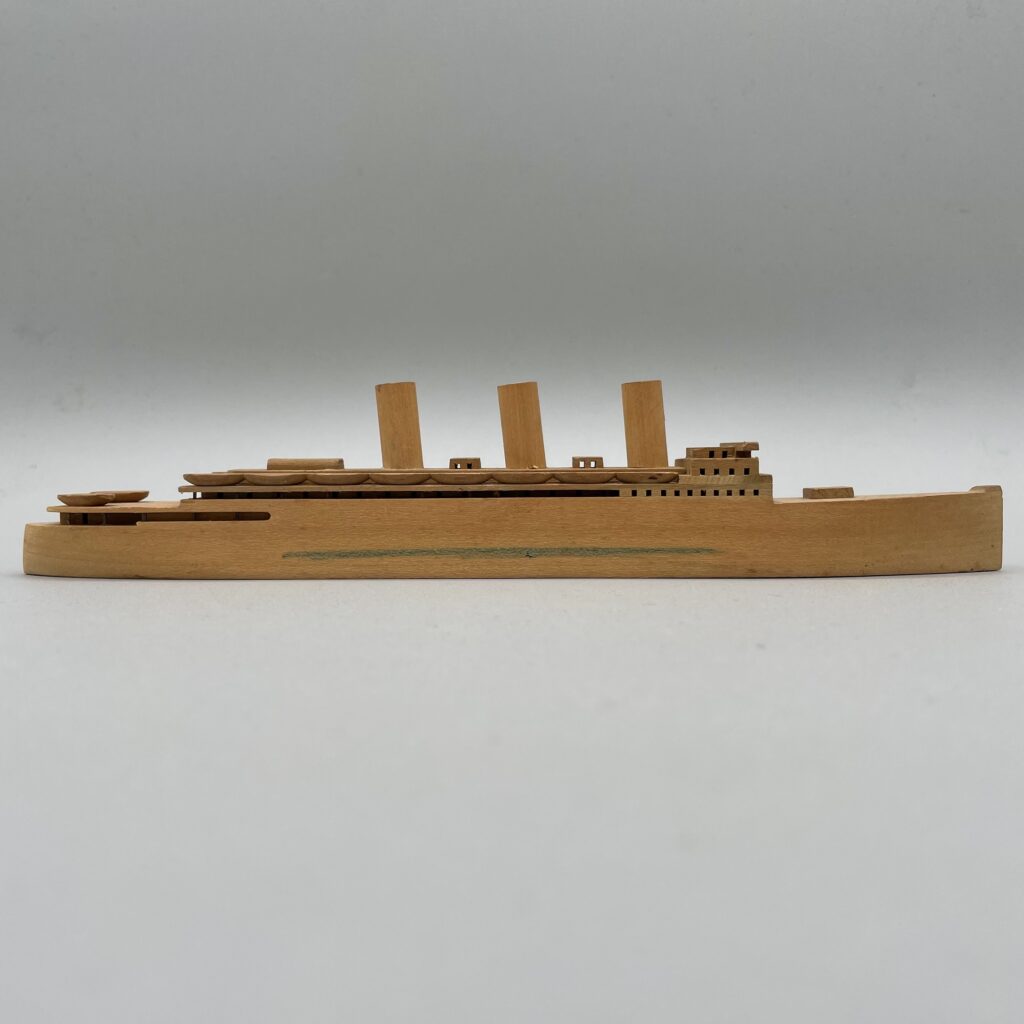

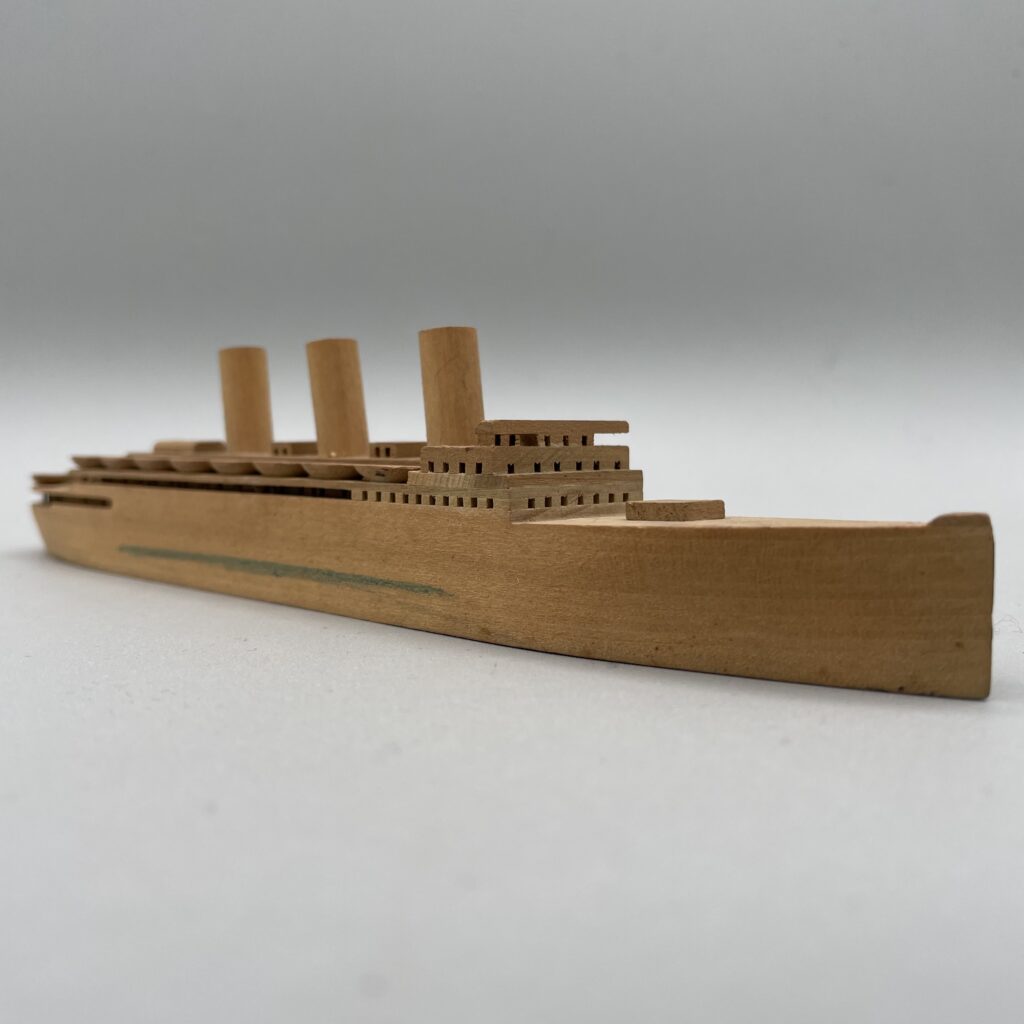

So what exactly is a “pattern model”? Pattern models were used by craftspeople in the shop as visual guides while building additional models of the same ship. Such types of ship models include little detail and are unpainted, representing only the waterline, and showing hull (the portion above water), super-structure, funnels, and lifeboats. Pattern models do not include masts, booms, king-posts, or ventilators, although these could be added later in production. Also noted in Anthony K. Van Riper’s donation letter is that none of the pattern models were intended for public sale.

Along with the acquisition material was an annotated catalogue of the pattern models, compiled by Anthony K. Van Riper and Janice P. Van Riper. Here, we receive a little more information about the details of the ship models. It is stated that the models are made of poplar and that the locations of not-included components, listed above, were represented on the plans of the models. We also learn that the reason for not including specific details had to do with the difficulty they caused in filing the models away at the model shop, i.e. less details make them easier to store.

The rest of the information in the catalogue tells us the name of the ship, its length, its original case, and any notes that may accompany it, such as what ship line it originated from. For example, the entry for scale ship model of RMS Empress of Asia tells us the ship’s name, its length, 9”, its original case, 4, and its notes that it is part of the Canadian Pacific Line and has a sister ship Empress of Russia.

Left: MV Emelia, ca. 1937-1952. Gift of Anthony K. Van Riper, 1982.019.0278

Center and right: RMS Empress of Asia, ca. 1937-1952. Gift of Anthony K. Van Riper, 1982.019.0164

Now that we have the background of the collection, let’s move on to the process of cataloguing.

Cataloguing 101

In a perfect world, donations would be accessioned and catalogued upon their arrival to the Museum. But, as we know, things are often far from perfect. Although the Van Ryper collection of pattern models donated by Anthony K. Van Riper arrived in the 1980s, the individual models had yet to be fully catalogued in the Museum’s collection management database, CollectorSystems. This is where my job came in!

How do you begin cataloguing a collection that has gone relatively untouched for forty years?

First, you must identify the information you want to complete. After talking with the Director of Collections and the Manager of Collection Information here at the Museum, we identified some key fields for collection information, as well as object care needs such as the need for every ship model to be photographed, have dimensions taken, and receive a condition report.

There are also small details to check, like making sure the correct location is noted, and formatting is consistent for each entry.

…and sometimes, these are not small details!

For example, making the metadata for the models’ ‘maker’ consistent became a major conundrum. Should we categorize the objects with a maker or an artist? Typically, an artist is considered the creator of an object, usually of fine art. A maker is the manufacturer of the object. We determined that the Van Ryper models should have a maker and not a single artist, as Charles K. Van Riper was not directly responsible for the physical creation of the ship models. As noted by his descendants, he was not necessarily artistically inclined, and hired craftspeople to produce the models in the shop.

So, who do we list as the maker? What might seem like a simple answer turned into hours of research that still has not given a 100% confident answer. I needed to determine the official name of the ship model shop. What I found in our archival material, online resources, and articles by his descendants, were multiple variations of what could be an official name.

In fact, I found seven possibilities for an official title of the ship model shop. The variations include: “Van Ryper”; “Van Ryper of Vineyard Haven”; “Van Ryper Model Shop”; “The Van Ryper Ship Model Shop”; “Van Ryper Model Co./Van Ryper Co.”; “Van Ryper Ship Models”; and “Van Ryper Models”.

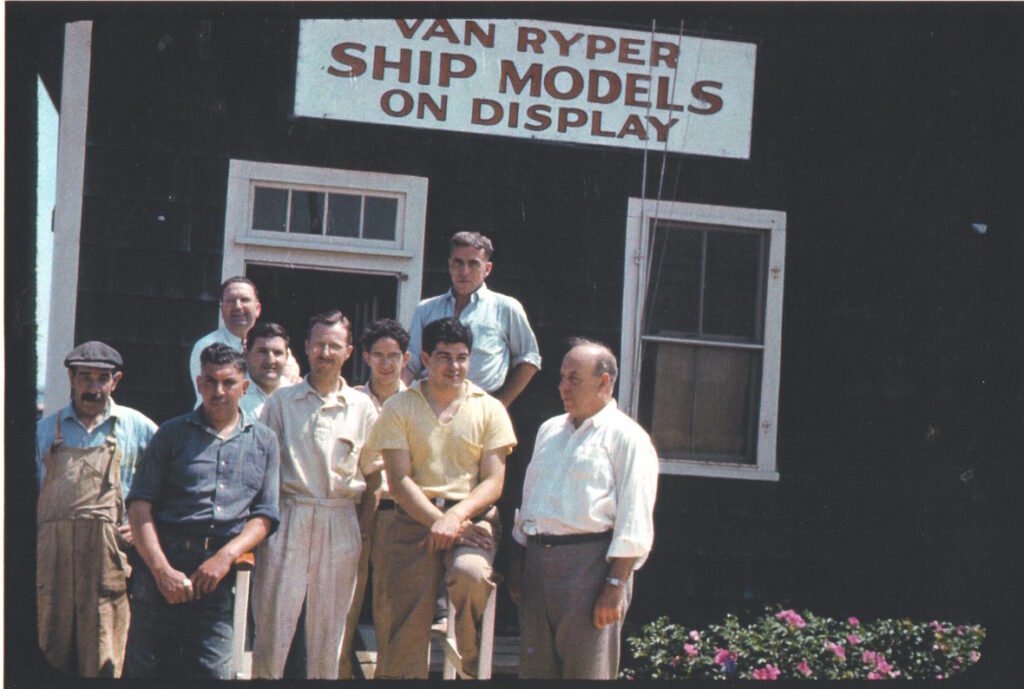

1930s Van Ryper shop crew. Image courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum

The first version, “Van Ryper”, proved to be most consistent throughout research material, appearing on a letterhead from Anthony K. Van Riper from 1981, in a letter from the acting curator during the time of the accession in 1982, in an article written by Anthony. K. Van Riper in The Duke County Intelligencer (Vol. 36, No. 2, November 1994), and in a Christie’s listing from 2008. It also appears in all variations of the name, and therefore we determined it was the best option to use in the official ‘maker’ category.

For every conundrum like the maker, I conducted research both online and through the Museum’s physical archives, looking for acquisitions, loans, and exhibitions resources, where brochures and other materials were re-discovered, like the annotated catalogue. This document offered a reference when working with the physical ship models, as I could cross check the physical inventory with the original inventory sheet, and see if there were any possible missing models, or unlisted models.

I also conducted research on Charles K. Van Riper, and the Van Ryper shop, online. This is where much of the background information that you just read above came from! While there is not much information about the shop or entrepreneur on the web, his son Anthony K. Van Riper, and grandson A. Bowdoin Van Riper were historians themselves, and each wrote about their relative’s life work.

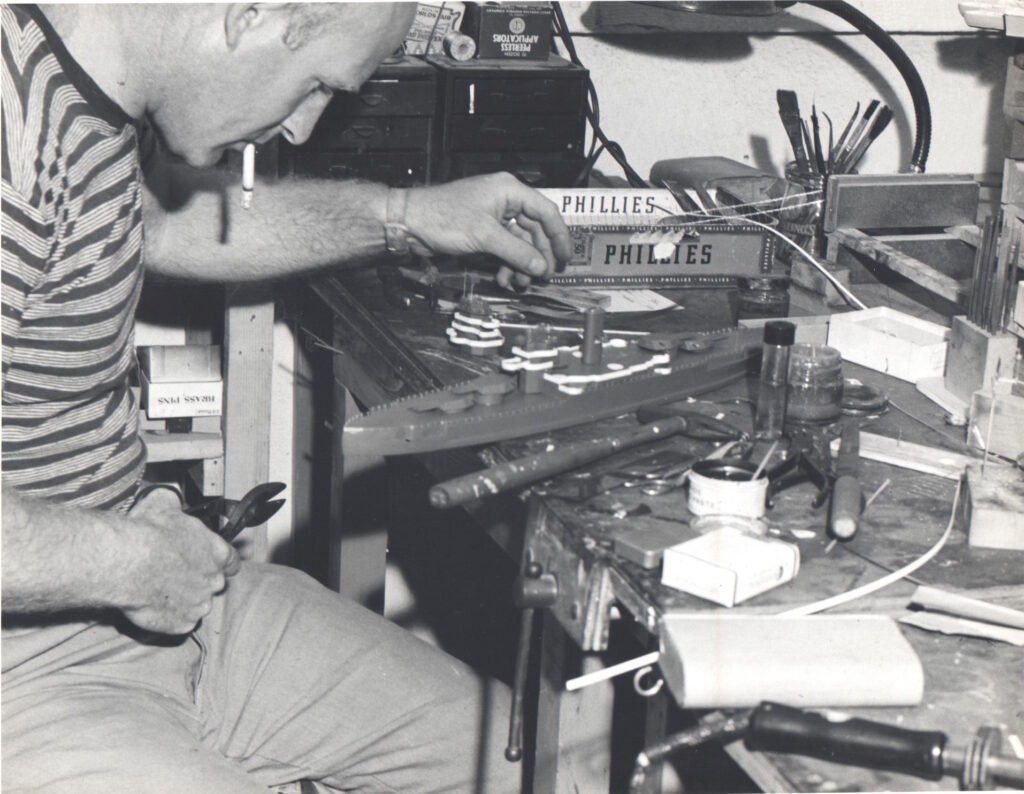

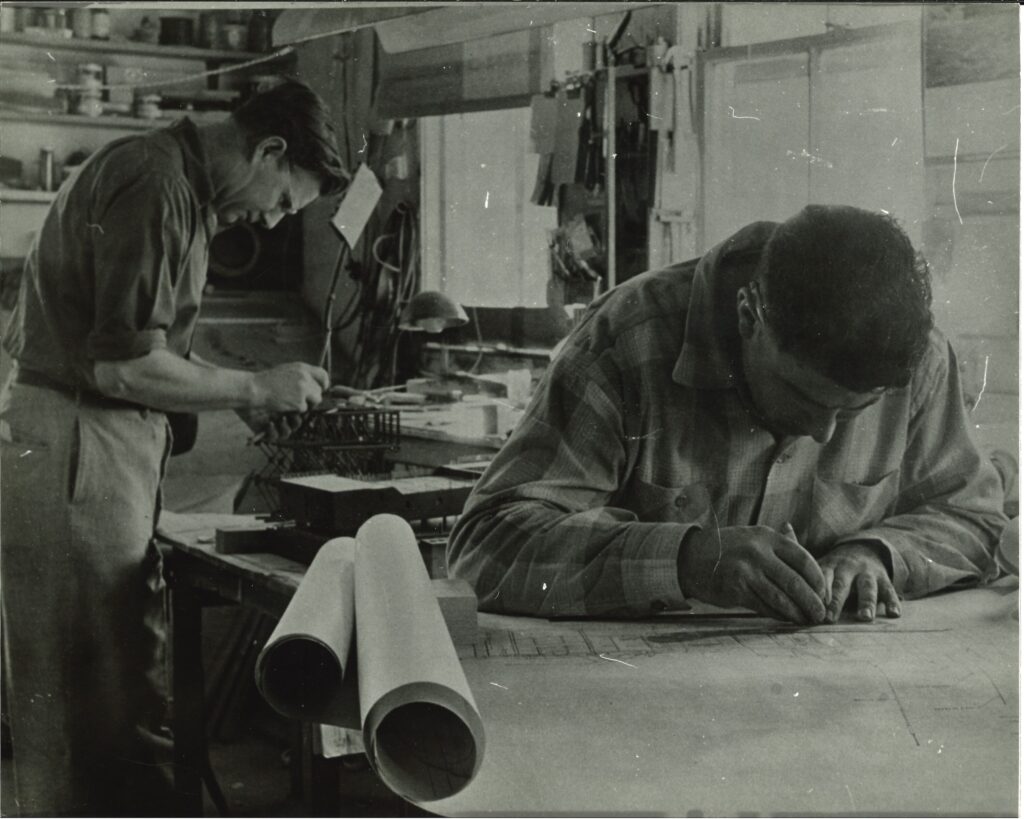

Eldon West and Cliff Dugan working in the Van Ryper shop. Image courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Museum

Why is all of this information important? Proper cataloguing allows the museum to have accurate and up to date information regarding the collection. In addition, once all of the information is correct, it can be published online for the public to see! Then, anyone interested in Van Ryper ship models will be able to see our collection and conduct research of their own!

Speaking of research, I also had to integrate the archival part of the donation. Processing papers is a little bit different from cataloging physical ship models.

The Archival Process

The archival materials had previously been accessioned under two different numbers, 1982.019.0286 and 1982.019.0287, noted in the original Deed of Gift as representing two drawers of research materials related to the business of the Van Ryper ship model shop. These two numbers would represent hundreds of individual pieces of paper, unlike the physical models which each received individual numbers.

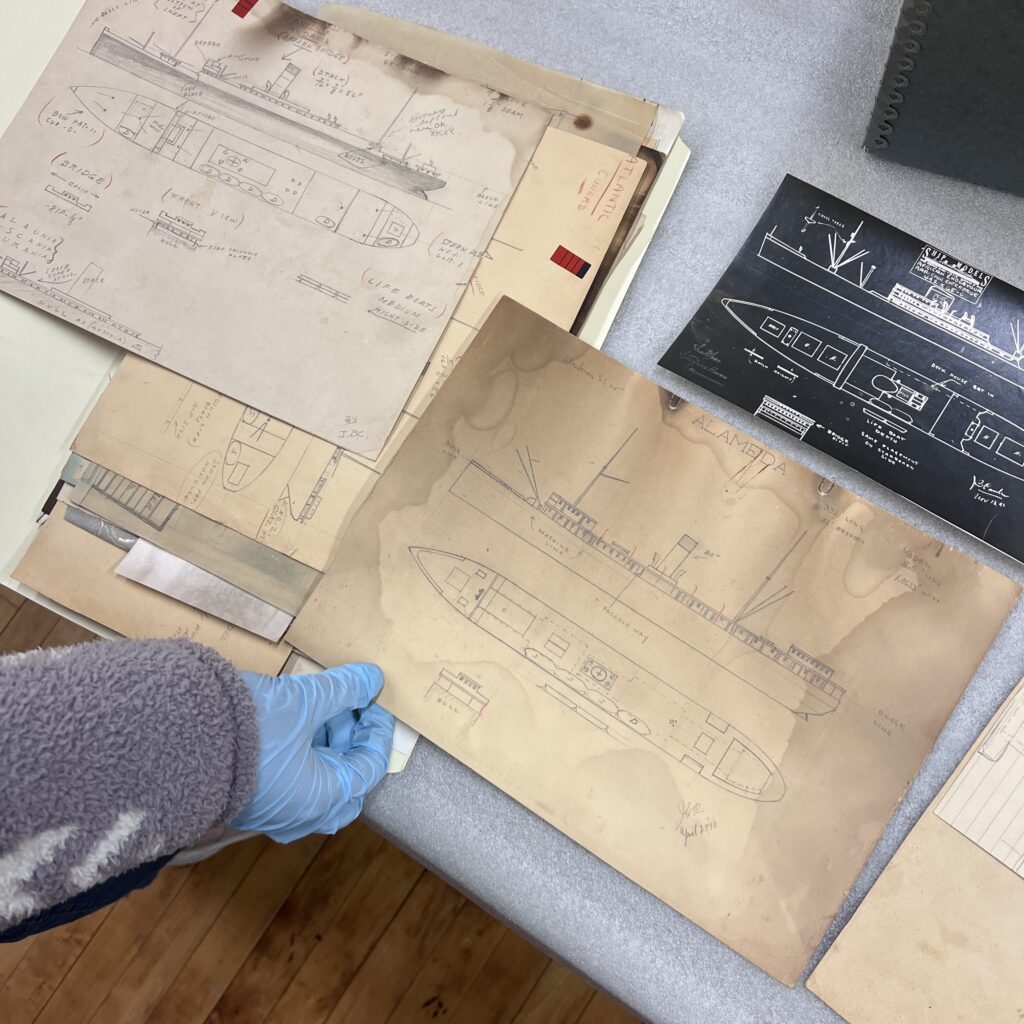

The documents were then reorganized at a later date. The number .0286 was categorized as ‘Van Ryper Research Materials’, while .0287 was titled ‘Van Ryper Ship Model Plans’. The research materials consist of Series 1-4: Correspondence, Brochures, Envelopes, and Order Forms. In total, Series 1-4 includes 141 items, dated 1934- 1959. The ship model plans are all under Series 5, with 25 subseries. Subseries 1-23 each represent letters of the alphabet A-W, while subseries 24 represents letters X, Y, Z, and subseries 25 is miscellaneous. In total, there are 487 items in Series 5, dated 1936- 1954.

Series 1 contains the correspondence of Van Ryper contacting shipping lines for descriptions of their vessels, visual references or ephemera. There are also examples of orders made by customers, including the Office of the President and the American Bureau of Shipping during World War II. Series 2 holds booklets and ephemera of the advertising of Van Ryper models. Series 3 has empty envelopes with the printed Van Ryper logo, and Series 4 holds blank order forms that would have been used to order models from Van Ryper. Series 5 ship model plans include hand drawn blueprints and drawings of ships, used to create the physical ship models.

Reorganizing the archival materials proved to be a little more difficult than imagined. We originally had two possibilities of how to go about the reorganization of the materials. The first option involved dispersing the archival materials into ‘components’, a section within the CollectorSystems database. This option would allow the research materials and ship plans to directly correspond with the models they represent. Option two consisted of adding new accession numbers to each archival material, so that they all would be individually accessioned and catalogued.

We did not end up going with either of these options. The troubles with the first option are that not all of the archival material have a physical ship model they correspond with, and it is somewhat against ideal archival practices. We also realized, concerning option two, that a large amount of the archival material had been dispersed into other parts of the Museum’s Reference Library, at a previous date. This realization came through reading the Deed of Gift, which stated that photographs, postcards, and deck plans/brochures from shipping lines were included in the archival material, none of which are currently present in our files. It also described that the materials were taken from two file drawers of materials, which we have less than half the volume of in our boxes.

What did we decide to do? We left the archival materials in their prior arrangement into ‘Research Materials’ and ‘Ship Model Plans’ and subsequent series. This means we did not have to create new entries for, or reorganize, the hundreds of archival images. We then cleaned up the information in the database for the two accession numbers and ensured consistency. Cleaning the entries included having an official item count, folder count, and checking for dated material. Next, we created a ‘group’ in CollectorSystems for all models that have matching plans and documents.

Throughout this process, we discovered that the Museum had an exhibition in 2003, Van Ryper: A World of Ships in Miniature. Some of the archival materials were found within the exhibition file, and had to be returned to their subsequent series.

Conclusion

As mentioned before, the donated collection of Van Ryper ship pattern models is vital to the collection of the South Street Seaport Museum. It provides a history of almost every ocean liner that traveled to the United States between 1900–1950, which is almost all of the passenger ocean liners that made voyages during the 20th century, as travel by ship became increasingly limited with the rise of the airline industry. They also provide insight to the revolutionary model ship making techniques that Van Riper implemented at his shop, to mass produce quality models that everyday-people could afford.

Now part of the Museum’s collection, the pattern models, once meant for the eyes of only the craftspeople, can be shared with the public as historical tools of miniature model ship making.

Van Ryper models also pay homage to the memories and voyages the real ships traveled. Something we can all relate to is the desire to hold on to, and cherish, memories of one’s life, which Van Ryper model ship souvenirs represent.

Additional reading and resources

Van Riper, Anthony. 1994. “Van Ryper Model Shop, Builders of Tisbury’s Table Top Fleet.” The County Intelligencer 36, no. 2 (November): 51-65.

Van Riper, A. Bowdoin. 2020. “Van Ryper Ship Models (Vineyard Haven).” MVMuseum Quarterly 61, no. 3 (August): 20-21.

Van Riper, Bowdoin. 2017. “Toy Boat, Toy Boat, Toy Boat | Martha’s Vineyard Magazine.” Martha’s Vineyard Magazine.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.